Struggle for Independence

The early XIX century was marked by revolutionary movements that reduced the once extensive Spanish empire to two colonies, Cuba and Puerto Rico. Although there were pro independence movements since the beginning of the century, the island ties to Spain were reinforced by economic conditions and the strong presence of Spanish troops. When Spain, focused on its own internal problems, failed to implement promised reforms such as parliamentary representation in 1837, Cuban intellectuals explored other alternatives such as annexation to the United States and the establishment of various reform and independent movements.

The failure of these movements, growing disaffection with Spanish rule and strengthening nationalist feelings laid the groundwork for the wars of independence.

The October 10 1868 declaration of war called Grito de Yara marked the beginning of the Ten Year War, followed by the so-called Guerra Chiquita (1979-1880), both unsuccessful. A peaceful attempt towards autonomy failed when war erupted once more in 1895 under the leadership of José Martí, who had the support of Cuban emigrés in the United States.

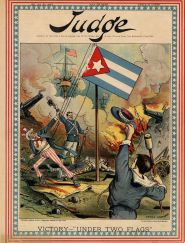

The War of 1895 devastated the island and its people. Increasing U.S. interests in Cuba had contributed to the interest of the American people in the situation, and the unexplained sinking in Havana's harbor of the battleship USS Maine on February 15, 1898 sealed the U.S. public's resolve for intervention. In 1898 the U.S. Congress issued a joint resolution declaring Cuba's right to independence, demanding the withdrawal of Spain's armed forces from the island and authorizing the use of force to secure that withdrawal. The Teller Amendment disclaimed any intention of annexation.

Spain declared war on the United States in April 1898 and the U.S. reacted in kind, thus starting the Spanish-American War. After the Spanish fleet suffered heavy losses the city of Santiago surrendered to General William Shafter on July 16, 1898, bringing an end to 400 years of Spanish rule. The Treaty of Paris, which officially ended the conflict, was signed on December 10, 1898 and approved by the U.S. Senate on February 6, 1899.

On January 1, 1899, the day the Spanish administration retired from Cuba, General John R. Brooke established a military government on the island.

Brooke’s administration restored much needed services such as sanitation and health to the war devastated island. General Leonard Wood headed the second period of American Occupation starting in December, 1899. Wood, whose top priorities were education, government reorganization and urban reconstruction, also continued health programs such as the eradication of malaria and yellow fever.

The transition towards independence was facilitated by the newly drafted constitution of 1900, which provided for universal male suffrage, a legislature and electoral procedures. This step towards independence, however, was undermined by the inclusion of the Platt Amendment, which gave the United States the right to intervene any time it deemed necessary, and also granted permanence to laws issued during the Occupation. After attempts by the Cuban Constituent Assembly to reject or modify it failed, the Amendment was ratified in 1901 and remained in force until 1934.