Cuban exiles arriving in Miami in the early 1960s typically settled in the city's southwest section, which became known as Little Havana. Cuban businesses quickly sprang up to fill the needs and interests of the growing émigré community, and Little Havana became the heart of Miami's Cuban exile enclave. Cubans also moved to nearby Hialeah, drawn by jobs at Miami International Airport and in the area's nonunion garment industry. In both of these geographic areas, entrepreneurial exiles established venues for entertaining the Spanish-speaking Cuban community.

Cuban theater in the early years of exile in Miami catered to the commercial tastes of a displaced audience looking for

ways to stay connected to the homeland they left behind and imagined returning to very soon.

Two popular theater genres in Cuba were sainetes,

one-act comedy sketches, often with music, and teatro bufo.

Teatro bufo, the longest ongoing theatrical tradition on the island dating to the 19th century, was a mix of slapstick comedy,

blackface, and political commentary. Another long-lasting genre favored by the Cuban public was lyrical theater,

which encompassed operas, zarzuelas, and light musical comedies.

one-act comedy sketches, often with music, and teatro bufo.

Teatro bufo, the longest ongoing theatrical tradition on the island dating to the 19th century, was a mix of slapstick comedy,

blackface, and political commentary. Another long-lasting genre favored by the Cuban public was lyrical theater,

which encompassed operas, zarzuelas, and light musical comedies.

Radio and television were the most important sources of entertainment in pre-revolutionary Cuba. They promoted a taste for slapstick humor and melodramatic comedies and drama. Among the exiled Cubans arriving in Miami were media founders, promoters, actors, and they were of paramount importance to the cultural formation of the exile community and the city. In the first half of the 1960s, comedy in Miami meant primarily sainetes and slapstick coming from the bufo tradition and television shows. By the mid-1960s, a sense of hopelessness about returning to Cuba had settled on the exile community. This was reflected in an increasing interest in activities driven by nostalgia for a pre-1959 Cuba.

At the Movies

The first theatrical presentations were staged during intermissions in movie theaters that showed double features of films originally in Spanish or subtitled.

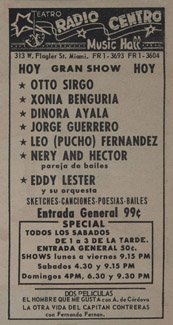

Several movie houses in Miami included Spanish-language films in their schedule, such as the Teatro Radio Centro (previously the Flagler Theater), Trail, Tower,

and Hialeah theaters. Named after a theater in Havana, Miami's Radio Centro presented variety shows, such as the one in this advertisement, that included theater sketches with

Cuban actors Otto Sirgo and Xonia Benguría, among others, and a screening of two movies.

The Bufo Tradition

The Bufo Tradition

These short performances were almost always comedies or vaudeville sketches. They counted on actors, singers, and entertainers

already known for their work in Cuban television, radio, and theater and were often

based on the popular bufo. The characters of el negrito in blackface and el gallego, the Spaniard as

exemplified by the Cuban comedy team of Alberto Garrido and Federico Piñero, who were well known for their characters Chicharito and Sopeira.

These early exile bufo sketches during intermissions provide an interesting parallel to the sainete tradition which used Afro-Cuban-based guaracha and danza, among other musical rhythms, to appeal to the working classes.

Leopoldo Fernández "Pototo" (1904-1985)

One of the most popular performers both in Cuba and among Miami exiles was Leopoldo Fernández.

He first appeared on the Cuban stage substituting Alberto Garrido in his famous role of el negrito

in Havana's Martí's Theater. The renowed comedic actor was expelled from Cuba's National Theater in 1963

and arrived in Miami on a Red Cross ship. This photograph shows Fernández (third from the right)

with the cast of the popular Cuban radio and television program, La tremenda corte, in which he

played the character of José Candelario "Tres Patines."

He first appeared on the Cuban stage substituting Alberto Garrido in his famous role of el negrito

in Havana's Martí's Theater. The renowed comedic actor was expelled from Cuba's National Theater in 1963

and arrived in Miami on a Red Cross ship. This photograph shows Fernández (third from the right)

with the cast of the popular Cuban radio and television program, La tremenda corte, in which he

played the character of José Candelario "Tres Patines."

Once in Miami, Fernández quickly started performing in local venues. One of his

early shows was a comedy at the Teatro Radio Centro in May 1963. As one of Cuba's

best-known humorists, he was a popular draw wherever he performed.

Leopoldo Fernández would go on to form his own theater company, Pototo y su Compañía Cubana,

performing comedies at theater venues across South Florida through the 1970s,

including the Teatro Lecuona in Hialeah.

Once in Miami, Fernández quickly started performing in local venues. One of his

early shows was a comedy at the Teatro Radio Centro in May 1963. As one of Cuba's

best-known humorists, he was a popular draw wherever he performed.

Leopoldo Fernández would go on to form his own theater company, Pototo y su Compañía Cubana,

performing comedies at theater venues across South Florida through the 1970s,

including the Teatro Lecuona in Hialeah.

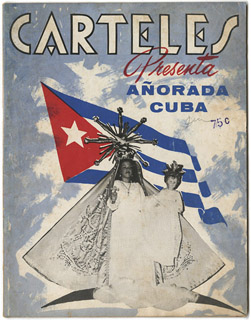

Añorada Cuba

The show that perhaps best represents the attitude of the first decade of exile and of the older generation of theater artists was Añorada Cuba (Yearning for Cuba). Performed by teenaged Cubans, traditional Cuban music, dance, and vignettes attempted to alleviate the pain of exile through a shared nostalgic experience while teaching Cuban cultural traditions to younger generations.

Añorada Cuba

Pili de la Rosa

In this interview, Pili de la Rosa,

one of the founders of Añorada Cuba, describes its beginnings as an

effort of the Immaculate Conception Catholic Church in Hialeah.

Demetrio Menéndez

Demetrio Menéndez

joined in the effort to launch Añorada

Cuba as its set designer. Here he describes how he started building stages and sets

for the show. Menéndez was to become the most important stage and set designer in

Miami during the 1970s and 1980s. He was hired by Margot Fonteyn to design the

stage and set for her ballet Romeo and Juliet, with which he travelled

all over the U.S. and Latin America.

Añorada Cuba

Carteles Internacional magazine dedicated an issue to Añorada Cuba:

"It is an instrument for the sentimental unity of Cuban people in exile.

Sixty percent of its earnings are invested in aiding the Cuban colony and the orphans or children whose

parents are subjugated by the red barbarism in an enslaved Cuba."

Carteles Internacional magazine dedicated an issue to Añorada Cuba:

"It is an instrument for the sentimental unity of Cuban people in exile.

Sixty percent of its earnings are invested in aiding the Cuban colony and the orphans or children whose

parents are subjugated by the red barbarism in an enslaved Cuba."

Asi es Cuba (This is Cuba) and Nuestra Cuba (Our Cuba) followed the footprint of Añorada Cuba with variety shows that included dance, music and short sketches.

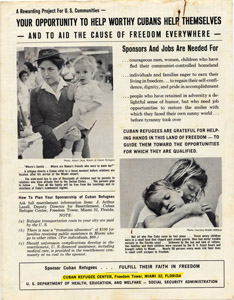

Most Cubans arriving in the United States during the 1960s assumed they would be staying only

temporarily. In pre-Revolutionary Cuba, close economic ties to the U.S. meant that the American

way of life permeated Cuban culture and social mores, including a more open stance towards

the rights of women. Since American values and ideologies were already a part of Cuban society,

many among the first generation of Cuban refugees in the U.S.

were better equipped to start a new life on American soil than most other immigrant groups.

Most Cubans arriving in the United States during the 1960s assumed they would be staying only

temporarily. In pre-Revolutionary Cuba, close economic ties to the U.S. meant that the American

way of life permeated Cuban culture and social mores, including a more open stance towards

the rights of women. Since American values and ideologies were already a part of Cuban society,

many among the first generation of Cuban refugees in the U.S.

were better equipped to start a new life on American soil than most other immigrant groups.

But even during a provisional stay, Cuban refugees had to survive, make money to feed families and care for children or elderly relatives, and simply get by. For most Cuban exiles, including those who on the island were part of the upper and middle classes and women who had never worked, this meant taking any job to be had. Theater artists were no exception, as demonstrated in the personal narratives in this section.

Néstor Cabell

Néstor Cabell,

one of the pillars of the early Miami-based Cuban theater,

arrived in New York in 1960. He moved to Miami in 1962 after being discharged

from the U.S. army. A well-known radio actor in Cuba, Cabell worked in exile in

factories, as a waiter, and as a delivery driver, among other blue-collar jobs.

In his free time, he would go to the airport to pick up his colleagues who were

arriving on a daily basis from Cuba.

Eva Vázquez (1915-2011)

Eva Vázquez was a famous performer who acted in all Cuban media since the 1930s. In this clip, she talks about her work in a furniture store

and with America's Production, the first company in Miami dedicated to dubbing films. America's Production also taped and

distributed radio programs in Spanish. Luis Boeri opened the company on the fifth floor of El Refugio (The Refuge), as

Miami's Freedom Tower was known among Cuban refugees. There, many of the recently arrived Cuban actors would record,

often working 13-hour days.

Ana Margarita Martínez Casado

In this picture taken on the set of the Cuban television show Cachucha y Ramón

Ana Margarita Martínez Casado is seated on the right. Born into a family of actors

and singers, she arrived in Miami after ten years of exile in Mexico. Her first job in the

U.S. was at Les Violins Supper Club

as a singing waitress, which allowed her to survive while she settled in Miami.

Asela Torres

Asela Torres, who would eventually become one of Miami's finest theatrical photographers as

evidenced by her photographs in this exhibit, worked in a cafeteria. Rejected as a

photographer by the producers of Nuestra Cuba (Our Cuba), a continuation of Añorada Cuba,

it was Manuel Urgarte and Alfonso Cremata of Teatro Las Las Máscaras who offered her the

first opportunity to photograph theatrical productions.

Luis Oquendo (1925-1992)

Radio, television, and film actor Luis Oquendo, became famous in the late 1970s

for his role on the bilingual PBS television show ¿Qué pasa, USA?.

Before that, he also worked as a dubbing actor, including voicing Clint Walker's character in Cheyenne.

In the credits for this 1967 program, both Luis Oquendo and Cecilio Noble are listed

as having worked for Voice of America, the official international

radio service of the U.S. government.

María Julia Casanova (1916-2004)

Theater pioneer María Julia Casanova, whose career spanned six decades in

Cuba and Miami, wrote several series for America's Production sponsored by Voice of America. In the midst of

the Cold War, Casanova and Jorge Jiménez Rojo wrote programs such as "El testigo" ("The Witness")

and "Nosotros, el pueblo" ("We, the People"), meant to be dramatic re-enactments of what was happening

in Cuba as a result of "tactics established by international communism."

She also wrote several pieces supporting the role of the United States in the Vietnam War.

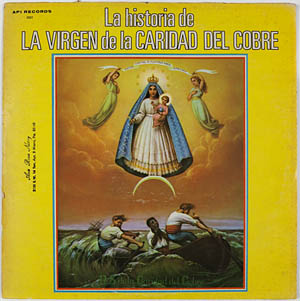

The Art of Giving

Working wherever they could to make ends meet did not stop theater artists from participating in

charitable activities. In the 1960s, the most important theater

voices in exile recorded an album to raise money to build a sanctuary

for the Virgin of Charity, the Patron Saint of Cuba. The sanctuary, along Biscayne Bay

in Coconut Grove, is still one of the most important cultural landmarks for

Catholic Cubans in the U.S.

Havana, Cuba, in the 1950s was one of the few places in Latin America where "art theater,"

mainly productions of European and American plays, and commercial theater successfully co-existed side-by-side.

mainly productions of European and American plays, and commercial theater successfully co-existed side-by-side.

Commercial imports from New York and Europe were common and enjoyed great success.

Commercial imports from New York and Europe were common and enjoyed great success.

By the second half of the 1960s, exiled artists began to experiment producing in Miami the "art theater" to which they were accustomed in Havana. At the same time, Cuban exiles strived to pass on to their children their heritage, their language, and their values, often through feasts and celebrations that borrowed from theater but were performed outside traditional theater spaces such as clubs, schools, and even on the street. Important among these events were the rituals associated with the Christian calendar, such as Nativity, Epiphany (or the day of The Three Wise Men), and the Resurrection.

Teatro 66

Teatro 66

Cuban theater in Miami started to move past comedies and nostalgic revues with the

launch of Teatro 66 by actor, educator, and director Miguel Ponce. In 1966,

he created the first Cuban "art theater" in Miami with a group of young

actors that included Salvador Ugarte, Norma Acevedo (later Norma Niurka),

and others. The poster shown suggests the material precariousness of the company.

In Teatro 66's founding letter,

it is stated that the company's goals were to recuperate Cuba's

theatrical tradition, including experimental and vanguard theater.

Teatro 67

In 1967, Teatro 67 (a transformation of Teatro 66) opened a sala-teatro (pocket theater) in Miami,

the first venue dedicated to Spanish-language theater in the city. This attempt at creating a

serious, non-commercial, experimental theater in the city had limited success.

The playwright and theater scholar Matías Montes Huidobro suggests that the exiled Cuban

middle class supported this kind of theater only sporadically. By 1968, most of Teatro 67's

founders had moved to New York, where many Cuban theater artists were creating a budding but

active off-off-Broadway theater movement in Spanish.

Teatro Las Máscaras

Teatro Las Máscaras

Salvador Ugarte and Alfonso Cremata, two student actors from Teatro 67,

stayed in Miami and founded Teatro Las Máscaras. The founding message included

in their first program called for the need to preserve Cuba's theatrical tradition

and bring to the "exile capital" theater from other Hispanic countries.

However, they would have to wait until the beginning of the 1970s to have their own space.

Teatro Martí

In 1967, entrepreneur Ernesto Capote converted what had been a boxing ring and the former home

of the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan into a space for the performing arts in Spanish. Like

other theaters of the time, Capote's Teatro Martí screened movies but also offered its space

to those interested in producing theater of any genre. While this theater became known

primarily for its comedies, this program for Medea, presented by Patronato del Teatro at the Martí,

demonstrates the range of theatrical productions it hosted and the need for "art theater" to

find spaces for their productions.

The Multifaceted María Julia Casanova María Julia Casanova worked in almost every area of the performing arts.

In addition to directing theater, she was a writer, lighting and stage designer,

and an architectural adviser. This guestbook

signed on May 29, 1974 by a "who's who" of the theater community

at the time honored Casanova for her achievements.

María Julia Casanova worked in almost every area of the performing arts.

In addition to directing theater, she was a writer, lighting and stage designer,

and an architectural adviser. This guestbook

signed on May 29, 1974 by a "who's who" of the theater community

at the time honored Casanova for her achievements.

Combining Technical Expertise and Artistic Vision

Cuban television star Manolo Torrente invited Casanova to help design a Tropicana-like show called Latin Fire Follies in Las Vegas.

The dance revue traveled across the U.S. during the late 1960s before finding a more permanent home in Las Vegas'

Thunderbird Hotel. Their final destination was Miami in 1983.

These drawings of the show's set are signed by the Japanese designer Ryotaro Mitsubayashi.

Another opportunity arose for Casanova when she received a contract to do the stage design for a Latin-themed show at the Paradise Island Casino Lounge in Nassau, The Bahamas. She trained the light technicians who remained in charge of the show once she returned to Miami.

Manuel Ochoa (1925-2006)

Manuel Ochoa, the famous Cuban virtuoso musician and choral and orchestral conductor, was essential in

unearthing the music of the Cuban composer Esteban Salas (1726-1803), especially his villancicos (Christmas carols).

De Belén a Bayamo: autosacramental cubano (From Bethlehem to Bayamo: A Cuban Oratorio) was Ochoa's

first work in exile with a script by María Julia Casanova.

Presented in 1968, it brought together religious celebration - in the message of Christmas - and patriotic feelings - in the 100th anniversary of the Cuban national anthem - by having the Holy Family and the Three Wise Men share the stage with Cuban independence leader Carlos Manuel de Céspedes and other illustrious characters. The music ranged from Handel, Schubert, and Beethoven to Cuban composers Muller, Garay and Figueredo.

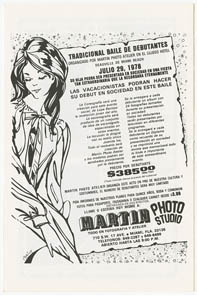

Social Stages

In addition to the founding of a theatrical culture, the reenactment of religious

and secular traditions such as The Three Wise Men (represented in Casanova's script)

and debutante balls (as seen in the ad in this theater program) were

important because they provided a sense of stability to a displaced people.

Cuban Heritage Collection

University of Miami Libraries

University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida

Feedback