After

emancipation, labor opportunities and experiences changed for the better.

Before emancipation a slave was lucky if he lived nine years after being

captured. Some died from diseases, but many of them died from simple

overwork. Plantation owners found it cheaper to work slaves

to death and buy new ones than to give them the food and rest they needed

to survive and reproduce. Slave

life on the plantation was an absolute nightmare. Some slaves worked

up to twelve hours straight without a break, under a  very

hot tropical sun. And the process of sugar making was not just hard

work but it was also dangerous. Because of the long hours worked some

slaves would fall asleep on the job. If that job was in the sugar mill

they could end up severely injured. A visitor to a plantation wrote

about how they handled serious injuries. The visitor was told by the

plantation owner that if a slave got his finger or arm caught in a mill

they would use a hatchet “that was always ready to sever the whole limb,

as the only means of saving the poor suffer’s

life.”

[1]

That is just a small portion of what slaves

had to go through. But better days were ahead for the slaves.

very

hot tropical sun. And the process of sugar making was not just hard

work but it was also dangerous. Because of the long hours worked some

slaves would fall asleep on the job. If that job was in the sugar mill

they could end up severely injured. A visitor to a plantation wrote

about how they handled serious injuries. The visitor was told by the

plantation owner that if a slave got his finger or arm caught in a mill

they would use a hatchet “that was always ready to sever the whole limb,

as the only means of saving the poor suffer’s

life.”

[1]

That is just a small portion of what slaves

had to go through. But better days were ahead for the slaves.

The

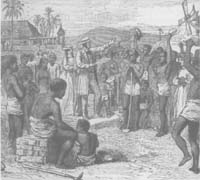

Emancipation Proclamation was read on August 1, 1834. There was plenty of singing, dancing,

and drumming to be seen and heard on that magical day. Many people celebrated

and the children added shouts “that seemed to rend the air.”

[2]

The Act of Emancipation “mandated in the first

instance large numbers of individuals were no longer slaves but neither

were they free citizens.”

[3]

Now there was a new hurdle, apprenticeship.

It was a turn from slave labor into a more acceptable, though still

mandatory form of labor, which would last four years.

The

Emancipation Proclamation was read on August 1, 1834. There was plenty of singing, dancing,

and drumming to be seen and heard on that magical day. Many people celebrated

and the children added shouts “that seemed to rend the air.”

[2]

The Act of Emancipation “mandated in the first

instance large numbers of individuals were no longer slaves but neither

were they free citizens.”

[3]

Now there was a new hurdle, apprenticeship.

It was a turn from slave labor into a more acceptable, though still

mandatory form of labor, which would last four years.

Apprenticeship

created several problems for the plantation owners. Slave owners were

used to working their slaves long hours. But

the days when owners could force slaves to work eighteen-hour days were

now no more. Apprentices could now only work forty hours

a week if they wished. Another problem was that many slaves used to

have to work the night shift. Emancipation put an end to that rule.

Blacks could now work four to five days a week and with the days they

had off, they could attend to their own gardens.

Of course, all too often the owners chose to ignore the new laws. The planters made no effort to change conditions

on the plantations. Getting new equipment and creating better working

conditions were out of the question. The plantation owners were expected

to supply medicine for the sick. That was not done. They were also expected

to supply better clothing and better food. Owners chose to ignore those

things as well. After emancipation the owners were given compensation

for their losses in human “property,” while ex-slaves received nothing.

Good

news came in 1837 when the apprenticeship was abolished. The planters

abused the system so much that it was terminated only after three years. More bad news came for the plantation owners.

The compensation that they received would not save most of them. Sugar prices continued to decline, even as production

went down because of the lack of workers. Instead of examining the situation

and admitting what was really wrong the planters decided to blame their

problems on the ex-slaves. The most often heard excuse was that blacks

were lazy and did not want to work anymore. The truth was that the ex-slaves

were finding new ways to make a living. They were tired of the working

conditions on the old plantations. They were sick of being treated with

cruelty. To many of them it was

time to move on. But some actually did stay on the plantations and tried

to make the best of it.

By

1860 half of the plantations in Jamaica had folded up. Many of the “plantations

were partly or wholly abandoned and the price of the property plummeted.”

The plantation owners only had themselves to blame. And with

the opening of the formerly protected British sugar market to free trade,

the few planters that survived “were forced to sell their crops on the

open market, often at a loss.”

[4]

By

1860 half of the plantations in Jamaica had folded up. Many of the “plantations

were partly or wholly abandoned and the price of the property plummeted.”

The plantation owners only had themselves to blame. And with

the opening of the formerly protected British sugar market to free trade,

the few planters that survived “were forced to sell their crops on the

open market, often at a loss.”

[4]

Former

slaves found new ways to make a living. Many of them became peasants

and formed villages and communities of their own. They began to grow

their own crops and sold them at the nearest markets. They grew ginger,

bananas, and sugar cane among many other crops. Of course the plantation

owners hated the fact that villages were springing up. These new villages

took away labor from them. The owners even found ways to get heavy taxes

placed on some of the most liked imported foods of the black man. And

as for American and British goods “the demand for linens, cottons, prints,

beaver hats, shoes, stockings, bonnets, and saddlery multiplied beyond belief.” But the heavy taxes placed on foreign goods

did not make the ex-slaves want to go back to the plantations.

[5]

At

first there were no schools or churches in the villages but that would

eventually change. After emancipation

“independent Negroes made the most of their income from growing provision

crops for sale in local markets.”

[6]

But other opportunities began popping up as

more and more villages were being built. The villagers were not just building houses for themselves.

They were building for others too. And these new structures were not

little huts either. Some had several rooms so that everybody in the

household could have their own room. As for dirt floors, that became

a thing of the past for many households. Some had wooden floors made

from the native trees on the island. With their houses built, black

Jamaicans soon turned their attention to extending their villages by

helping missionaries construct churches and schools. This would be the

beginning of something special. Education was just around the corner

for many.

were being built. The villagers were not just building houses for themselves.

They were building for others too. And these new structures were not

little huts either. Some had several rooms so that everybody in the

household could have their own room. As for dirt floors, that became

a thing of the past for many households. Some had wooden floors made

from the native trees on the island. With their houses built, black

Jamaicans soon turned their attention to extending their villages by

helping missionaries construct churches and schools. This would be the

beginning of something special. Education was just around the corner

for many.

Education

played an enormous role in the upward movement of many free citizens. Many

young men and women attended the schools that sprang up  around

the island. Some

went on to become teachers and educate the next generation.

Others became ministers and preached in the local

churches. This was a step up

from the labor their parents performed.

Some were able to obtain jobs tending to business matters on

the island. But not everybody the island was able to attend schools

and obtain jobs such as teaching, and not everybody left the world of

hard manual labor. Job opportunities off the island became enticing.

Many still had to work jobs where

physical strength was needed.

around

the island. Some

went on to become teachers and educate the next generation.

Others became ministers and preached in the local

churches. This was a step up

from the labor their parents performed.

Some were able to obtain jobs tending to business matters on

the island. But not everybody the island was able to attend schools

and obtain jobs such as teaching, and not everybody left the world of

hard manual labor. Job opportunities off the island became enticing.

Many still had to work jobs where

physical strength was needed.

Panama was one such place where workers

were needed. A railway was needed there. But for the Jamaicans that

went, the great job opportunity turned into a nightmare. The Jamaicans were not the only ones who went

to Panama “to cut a canal across the Isthmus

in 1879.” Others such as the

Chinese and Europeans also went. Disease

was rampant and the deadly yellow fever was the worst of those illnesses. The Jamaicans and the West Indians “stood up

better to the fever, but a great many died, nevertheless, and within

nine years, after a shocking waste of life and money, the canal scheme

collapsed.” Many of those who

survived stayed in Panama. When the United States decided to build a canal in Panama in the early twentieth century many

Jamaicans again lent a hand in the construction of the canal.

[7]

Ex-slaves

and their children made many strides after emancipation. Life was not

easy for most of them but with ambition and pride came

success for many. Going from plantation work to becoming teachers and

ministers was not an easy or short journey. Freedom was something for

which they had been longing, and when it came they made the most of

it. All they needed was a chance and emancipation gave them that chance.

Many found that life could be something beautiful.

Works Cited

Craton, Michael and Walvin, James. A Jamaican Plantation: The History Of

Worthy Park 1670-1970. Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1970.

Nugent, Maria, Lady. A Journal Of A Voyage To, And Residence

In, The Island Of Jamaica,

From 1801 To 1805, And The Subsequent Events In England from 1805 To

1811, By Maria, Lady Nugent. London: T. and W. Boone, 1839.

Papers Relative To The West Indies 1841. Part II Jamaica. London: W. Cloves and Sons. 1841.

Phillippo, James Mursell.

Jamaica: Its Past

And Present State. Philadelphia: J.M. Campbell And Co., New York: Saxton and Miles, 1843.

Sherlock, Philip and Bennett, Hazel.

The Story Of The Jamaican People. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers, Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 1998.

[1] Maria Nugent, A Journal Of A Voyage

To, And Residence In, The Island Of

Jamaica, From 1801 To 1805, And The Subsequent Events In England from

1805 To 1811, By Maria, Lady Nugent, (London, 1839,) 151.

[2] James M. Phillippo,

Jamaica: Its Past And Present State, (Philadelphia and New York, 1843,) 71.

[3]

Philip Sherlock and Hazel Bennett, The

Story Of The Jamaican People, (Kingston and Princeton, 1998,) 230.

[4] Sherlock and Bennett, 233.

[5]

Parliament, Papers Relative To The West Indies 1841. Part II Jamaica, (London, 1841,) 174.

[6] Michael Craton

and James Walvin, A

Jamaican Plantation: The History Of Worthy Park 1670-1970, (Toronto and Buffalo, 1970,) 215.

[7] Quotes from Clinton V. Black, History

of Jamaica, (London,

1958/1970,) 221.