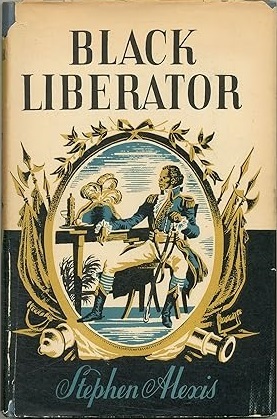

Historical Heritage

Stéphen Alexis, Haitian diplomat, and father of Jacques Stéphen Alexis

New York: Macmillan Co., 1949

Abridged translation of the author’s “Toussaint Louverture, libérateur d’Haiti” by William Stirling

“Toussaint Louverture, Libérateur d’Haiti,” the original work from which “Black Liberator” has been abridged into an English translation, is a much longer book, abounding in the reflections of the author, himself a noted Haitian diplomat and writer, on the destiny of Toussaint and the Negro race.

… It is difficult to realize today the enormous importance to Europe of the West Indian islands 150 years ago. This explains the constant interest and anxiety shown by France over Saint-Domingue (the present Haiti), her wealthiest colony. The wealth was dependent upon the institution of slavery, and the Negroes were considered to be scarcely human, even by enlightened men and women. Hence the complete lack of moral discipline in the relations of most white planters to their slaves, and the unashamed profligacy which led to the creation of the mulatto race, with all its political consequences in the island. Against this historical background the magnitude of Toussaint’s achievements and those of his associates becomes intelligible, as does the subsequent stormy History of Haiti, now happily free and at peace.

— From the preamble

Stéphen Alexis

Butterfly Publications, 2013

English translation of excerpt by Béatrice Colastin Skokan, Libraries, University of Miami

Stéphen Alexis was a Haitian writer, activist, diplomat, and the father of Jacques Stéphen Alexis. His letter, to his friend Antoine Rigal, is referring to their respective imprisonments during the American occupation. Alexis dedicated the book to the Haitian revolt led by Charlemagne Péralte, and his followers called the “Cacos” against the American occupation of Haiti (1915–1934).

"My dear Antoine Rigal,

Do you remember that accursed afternoon, when in the hell of the Rue du Centre—you too, prisoner of the American occupation—dropped, while passing by the fence of the dungeon where I was almost dying of hunger, a piece of bread? It was in June 1918. I had been, at the beginning of the month, arrested at Ennery and brought to Port-au-Prince, by a transport of the American navy, the “Potomac”, under the pretext that I was going to echo the heroic revolt of Charlemagne Péralte against the oppressor. You have certainly not forgotten this painful period of our life.

As gratitude for that piece of bread, I would have dedicated this work to you that contains a few scenes, torn from a terrible reality, if the memory of the legendary hero, so dear to both of us, did not prohibit your name at the frontispiece of this book that is less a novel than a succession of little human documents.

Cordially,

Stéphen Alexis

Port-au-Prince, December 10th, 1933."