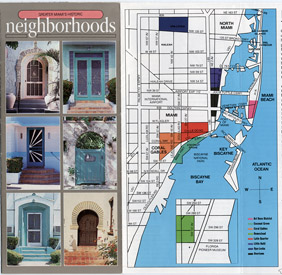

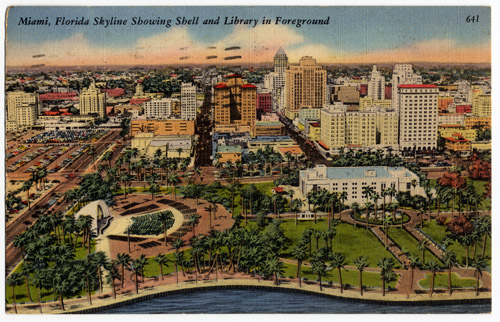

Miami underwent a radical transformation in the second half of the

20th century. By the early 1970s, other Latin Americans started to

make Miami their home.

The Spanish speaking population grew by 2,000%

between 1960 and 1990, when it became the majority of the population.

Language turned out to be an important issue, both at the local level with an

ordinance passed in 1973 proclaiming then-Dade County a bilingual

community, and also in the sphere of theater, where artists and

audiences grappled with the question if plays written in a language

other than Spanish could be considered Cuban.

The Spanish speaking population grew by 2,000%

between 1960 and 1990, when it became the majority of the population.

Language turned out to be an important issue, both at the local level with an

ordinance passed in 1973 proclaiming then-Dade County a bilingual

community, and also in the sphere of theater, where artists and

audiences grappled with the question if plays written in a language

other than Spanish could be considered Cuban.

This section tells the story of how Spanish Miami, by the end of the 1970s, had evolved from being mainly a community of Cuban exiles to a cosmopolitan urban center. It articulates this growth, the pains associated with it, and the transformation of the Cuban community that survived by creating art forms that could embrace all the contradictions of human experience, in addition to those caused by the duress of exile.

As Miami became the Cuban exile capital during the 1960s

and 1970s, two currents met on Miami's stages to enhance the

city's theatrical life. The first current saw some artists

drawing on emotions and memory to reconstruct a past they

could hardly leave behind as they tried to make sense of

the present. Whether on the island, as in the case of

Virgilio Piñera, or in exile, as with the already established

playwrights who left Cuba during the 1960s such as Julio Matas

and Matías Montes Huidobro, these writers went back to pre-revolutionary avant-garde theater.

As Miami became the Cuban exile capital during the 1960s

and 1970s, two currents met on Miami's stages to enhance the

city's theatrical life. The first current saw some artists

drawing on emotions and memory to reconstruct a past they

could hardly leave behind as they tried to make sense of

the present. Whether on the island, as in the case of

Virgilio Piñera, or in exile, as with the already established

playwrights who left Cuba during the 1960s such as Julio Matas

and Matías Montes Huidobro, these writers went back to pre-revolutionary avant-garde theater.

At the same time, another current saw a new generation of writers emerge with dramatic expressions that denoted a new Cuban-American identity, oftentimes rediscovering theater as a site of contention and reflection about the exile condition. Cuban-American dramaturgy took off, and theater directors tended to favor this theatrical expression over Cuban exile drama.

The First Exile Play

Pedro Román's Hamburgers y sirenazos (Hamburgers and Siren Blasts)

debuted in 1962 and it was staged repeatedly during the 1960s as part of the Añorada Cuba programs. It later

appeared in 1970's Una noche con Cuba (A Night with Cuba).

Using comedy, it was the first play written in exile to address

the plight of a Cuban family transplanted into South Florida.

In subsequent theater productions, Román moved towards the

vernacular genre with titles such as Miami es un vacilón

(con Cheo en la Comisión) (Miami is a Lot of Fun with

Cheo in the Commission).

appeared in 1970's Una noche con Cuba (A Night with Cuba).

Using comedy, it was the first play written in exile to address

the plight of a Cuban family transplanted into South Florida.

In subsequent theater productions, Román moved towards the

vernacular genre with titles such as Miami es un vacilón

(con Cheo en la Comisión) (Miami is a Lot of Fun with

Cheo in the Commission).

Keeping Cuba Alive Luis Oquendo's Los Inocentes (The Innocent Ones), written by

Griselda Nogueras and Vivian García, played at the beginning

of the 1970s at the Ada Merritt School Auditorium.

Using quotes from 19th century figures such as José Martí,

Máximo Gómez, and José Sanguily, the play provided an

ideal frame to address current events in Cuba when some

segments of the exile community were losing interest

on the internal affairs of the island. The play reached

its highest dramatic moment when the voice of Pedro

Luis Boitel's mother accused the Cuban government

of her son's assassination. Boitel was a political

prisoner in Cuba who died during a prison hunger strike in 1972.

Luis Oquendo's Los Inocentes (The Innocent Ones), written by

Griselda Nogueras and Vivian García, played at the beginning

of the 1970s at the Ada Merritt School Auditorium.

Using quotes from 19th century figures such as José Martí,

Máximo Gómez, and José Sanguily, the play provided an

ideal frame to address current events in Cuba when some

segments of the exile community were losing interest

on the internal affairs of the island. The play reached

its highest dramatic moment when the voice of Pedro

Luis Boitel's mother accused the Cuban government

of her son's assassination. Boitel was a political

prisoner in Cuba who died during a prison hunger strike in 1972.

Different Voices on Stage

Tony Wagner's 1978 production of Josefina, atiende a los señores:

cuentos y cortos (Josefina, Take Care of the Gentlemen:

Short Stories and Fragments), put on the stage three different

voices: Pedro Ramón López who founded the exile magazine Nueva

generación; Cuban-American author Roberto G. Fernández, known

for his parodies of Miami's diasporic experience; and the

irreverent, accomplished exiled novelist Guillermo Cabrera

Infante (1929-2005). The latter's short story, which lends its title to the production,

deals with sexual exploitation of women in a patriarchal society,

Short Stories and Fragments), put on the stage three different

voices: Pedro Ramón López who founded the exile magazine Nueva

generación; Cuban-American author Roberto G. Fernández, known

for his parodies of Miami's diasporic experience; and the

irreverent, accomplished exiled novelist Guillermo Cabrera

Infante (1929-2005). The latter's short story, which lends its title to the production,

deals with sexual exploitation of women in a patriarchal society,

a topic rarely addressed in a milieu saturated by images

of women in equivocal situations.

a topic rarely addressed in a milieu saturated by images

of women in equivocal situations.

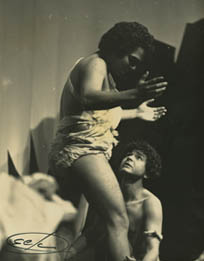

Night of the Assassins in Miami

José Triana's

La noche de los asesinos (Night of the Assassins, 1964) was awarded Cuba's

prestigious Casa de las Américas Prize in 1965, and it became an instant success

on the island and abroad. Tony Wagner - by then a regular in Miami's playhouses

-- brought it to Miami in 1977 and 1978 with Teatro Prometeo. His

staging placed the characters in a boxing ring to underscore the

repressive family as a microcosm of post-revolutionary Cuba. Wagner's production was followed by at least two stagings by Teatro Avante

during the 1980s, one directed by Alberto Sarraín and the other by Rolando Moreno.

Children's Theater

Children's Theater

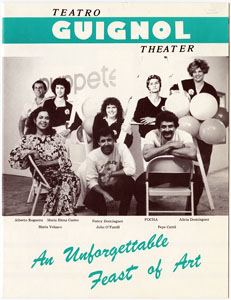

The first activities of the Promethean Players, as they were known in English,

included a presentation during Christmas of a famous Latin American children's story,

La Cucarachita Martina (Martina: The Tiny Bug). They performed it in Spanish in the morning

and English in the afternoon. All of Prometeo's productions were free-of-charge until 1983,

when they set their ticket price at $3.00.

Performing Bilingualism

Performing Bilingualism

Bilingualism became an issue addressed by necessity,

especially in productions directed at younger audiences,

whose first language in many instances was already English.

One of the first bilingual plays produced in Miami was Prometeo's

Chimpete-Champata & Chi-Cheñó. With this play, they tried "to reach

a rhythm whereas the two languages would be intertwined becoming one,

but avoiding Spanglish," according to Teresa María Rojas.

The show wanted black, white, and brown hands to unite, forming

an unending dancing line, making circles led by small animals to the sounds of children's music.

Cuban-American Characters Speak

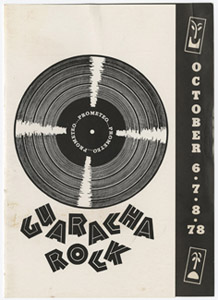

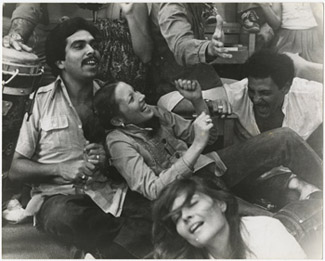

Prometeo's 1978 production of Guaracha Rock was probably one of the first instances in which Cuban-American

characters took center stage in Miami. In this "documentary" performance, Promethean Players had the opportunity to express the pain and pleasures of their adolescence, including

the use of drugs as a coping mechanism. The play used popular Cuban and American

music to underscore bicultural identities.

Cubans and the American Dream

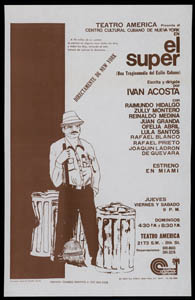

Iván Acosta' El Super (The Superintendent) also opened in Miami in 1978 after a first showing in New York City,

where it was written. New York already enjoyed the presence of notable Cuban-American

playwrights such as María Irene Fornés and Dolores Prida and exiled writers such as

José Corrales and Manuel Pereiras. In the play El Super, a father spends the northern

Iván Acosta' El Super (The Superintendent) also opened in Miami in 1978 after a first showing in New York City,

where it was written. New York already enjoyed the presence of notable Cuban-American

playwrights such as María Irene Fornés and Dolores Prida and exiled writers such as

José Corrales and Manuel Pereiras. In the play El Super, a father spends the northern

cold winter days dreaming of the warm weather of his native land, while his Americanized daughter

wants no part in his plans of going "back" to Miami. The play is one of the earliest examples

in which the American Dream is put into question on the Cuban Miami stages.

cold winter days dreaming of the warm weather of his native land, while his Americanized daughter

wants no part in his plans of going "back" to Miami. The play is one of the earliest examples

in which the American Dream is put into question on the Cuban Miami stages.

Questioning the Exile Experience

Questioning the Exile Experience

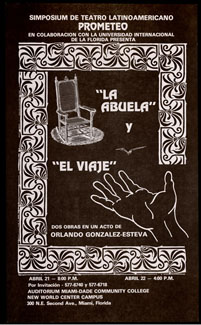

One of the earliest examples of introspection about the exile experience in

Cuban-American theater was Prometeo's 1979 production of Orlando González Esteva's La vieja

(The Old Lady) and El viaje (The Trip). La vieja visited the figure of the grandmother who

traditionally is seen as the central pillar of the home. El viaje, according to Gloria Waldman,

"revives the protagonist's departure from Cuba when he was 12 years-old, lyrically calling back

the world of his childhood. The dramatic force of the piece resides in the counterpoint

established between his remembrances and the present day world" (El Nuevo Día, June 19, 1979).

The Reunion Begins

The reencuentro or reunion topic entered Cuban theater at the end of the decade,

with the initiation of dialogue between Cuban authorities and segments of the

exile community. It took off with René Alomá's A Little Something to Ease the

Pain (1979) in which a young man returns to his native city of Santiago de Cuba

to find "answers" among the relatives that stayed behind. It premiered in Toronto's

Centre Stage in 1980. Its Spanish version, Alguna cosita que alivie el sufrir,

was translated and directed by Alberto Sarraín, with its Miami premiere by Teatro Avante in 1986.

Politically, the 1970s were a time of entrenchment and militancy

among certain segments of Miami' exile population.

Direct violence

such as bombings and assassination attempts against those who

demonstrated anything but total opposition to Cuba's Castro

regime gathered momentum. While the end of the decade saw a

change in popular opinion recognizing terrorism as a stain on

the image of the Cuban exile community, a decrease in direct

violence did not mean an end to hardline reactions.

Politically, the 1970s were a time of entrenchment and militancy

among certain segments of Miami' exile population.

Direct violence

such as bombings and assassination attempts against those who

demonstrated anything but total opposition to Cuba's Castro

regime gathered momentum. While the end of the decade saw a

change in popular opinion recognizing terrorism as a stain on

the image of the Cuban exile community, a decrease in direct

violence did not mean an end to hardline reactions.

In the theater sphere, if a work's politics were not clearly

anti-Castro or the artists' views plainly anti-communist,

hardliners staged protests and boycotts against shows deemed

controversial and used Spanish-language media to decry them.

The fact that there was a strong audience base for controversial

shows and that these acts of symbolic (and sometimes real) violence were decried

demonstrated that while the prevailing conservative voice

controlled Miami's Cuban community Spanish-language media,

it was not the only one.

In the theater sphere, if a work's politics were not clearly

anti-Castro or the artists' views plainly anti-communist,

hardliners staged protests and boycotts against shows deemed

controversial and used Spanish-language media to decry them.

The fact that there was a strong audience base for controversial

shows and that these acts of symbolic (and sometimes real) violence were decried

demonstrated that while the prevailing conservative voice

controlled Miami's Cuban community Spanish-language media,

it was not the only one.

Ñángaras (Zealots) Shown here is an annotated copy of an article that appeared in the

Cuban and international press in 1960. The "Manifesto of

Intellectuals and Artists" was signed by prominent Cuban

figures and called for the revolutionary creation of a

national culture. This copy was anonymously annotated by

someone who underlined in red the names of those signatories

Shown here is an annotated copy of an article that appeared in the

Cuban and international press in 1960. The "Manifesto of

Intellectuals and Artists" was signed by prominent Cuban

figures and called for the revolutionary creation of a

national culture. This copy was anonymously annotated by

someone who underlined in red the names of those signatories

considered to be communists, such as Virgilio Piñera, Rosa Felipe,

Herberto Dumé, and Griselda Nogueras, and included the

epithets rojo (red) and ñángara (communist revolutionary zealot).

considered to be communists, such as Virgilio Piñera, Rosa Felipe,

Herberto Dumé, and Griselda Nogueras, and included the

epithets rojo (red) and ñángara (communist revolutionary zealot).

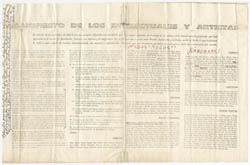

"Red Like her last name"

Prometeo's first production was Graham Greene's El león dormido (The Sleeping Lion)

in 1974. A recreation of the Faustus myth, the play had nothing to do with politics,

yet Rojas was accused of being a communist because she had chosen to stage

an author that had visited Cuba in the early 1970s.

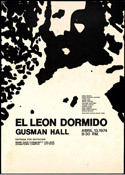

Paper Flowers and "Red Cuba"

The U.S. premiere of Egon Wolff's Flores de papel (Paper Flowers,

1970) by Teatro Prometeo in 1975 also caused concern in

the Cuban exile community. The play addressed the creative

and destructive forces of artistic creation, a theme of

interest to the Promethean Players. It had ample press

coverage since it was the first time Francisco Morín directed

in Miami. However, several small newspapers ran editorials

condemning the author for having accepted a prize in "Red Cuba."

A warning to then Mayor Maurice Ferré in the exile newspaper La

verdad also defamed Rojas for not being trustworthy. The publication

Libertad, on the other hand, chose this production and Francisco

Morin's direction as the best of 1975.

1970) by Teatro Prometeo in 1975 also caused concern in

the Cuban exile community. The play addressed the creative

and destructive forces of artistic creation, a theme of

interest to the Promethean Players. It had ample press

coverage since it was the first time Francisco Morín directed

in Miami. However, several small newspapers ran editorials

condemning the author for having accepted a prize in "Red Cuba."

A warning to then Mayor Maurice Ferré in the exile newspaper La

verdad also defamed Rojas for not being trustworthy. The publication

Libertad, on the other hand, chose this production and Francisco

Morin's direction as the best of 1975.

Caught in "the Cuban Thing"

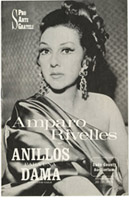

Spanish star Amparo Rivelles was involved in a controversy

for bringing about the substitution of two well-known Cuban actors in Grateli's 1975

production of Antonio Gala's Anillos para una dama (Rings for a Lady),

claming that the actors did not know their lines.

Detractors

Spanish star Amparo Rivelles was involved in a controversy

for bringing about the substitution of two well-known Cuban actors in Grateli's 1975

production of Antonio Gala's Anillos para una dama (Rings for a Lady),

claming that the actors did not know their lines.

Detractors

interpreted her decision and comments as being anti-exiles,

suggesting that her apparent anti-Franco stance meant she was

pro-communist. The controversy resurfaced every time the actress visited Miami.

As late as 1978, the exile publication La nación published a mock obituary

of Rivelles stating: "True Cubans do not forget the offense that you

inflicted upon us through the brilliant artists Rosa Felipe and Miguel

Angel Herrera. Do not forget that Cuba was the one that opened the

doors of America to you (August 11, 1978, p. 19)."

interpreted her decision and comments as being anti-exiles,

suggesting that her apparent anti-Franco stance meant she was

pro-communist. The controversy resurfaced every time the actress visited Miami.

As late as 1978, the exile publication La nación published a mock obituary

of Rivelles stating: "True Cubans do not forget the offense that you

inflicted upon us through the brilliant artists Rosa Felipe and Miguel

Angel Herrera. Do not forget that Cuba was the one that opened the

doors of America to you (August 11, 1978, p. 19)."

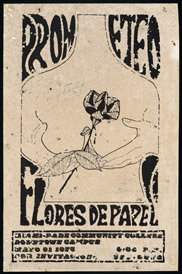

Prometheus's Unclear Message

Teatro Prometeo's 1976 staging of the play Prometeo (Prometheus), written by Tomás Fernández Travieso,

a political prisoner in Cuba, generated a paradoxical controversy. Although the play's

production meant an additional five years in prison were added to Fernández Travieso's

sentence, polemic arose because some critics believed that the play did not have a clear

political message. Others, however, wrote editorials in the Spanish press and personal

letters to Rojas commending her for the production.

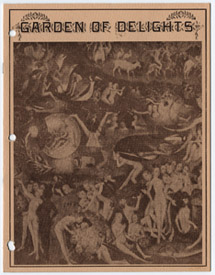

No Indecency on Our Stages

The controversy surrounding Prometeo's two stagings of

works by Fernando Arrabal during this period, Fando

and Lis in Spanish (1976) and The Garden of Delights

in English (1978), conflated issues of decency and politics.

Arrabal, an important Spanish avant-garde playwright, was

branded a communist because of his anti-Franco position.

Critics cautioned potential theatergoers against going to

see The Garden of Delights because it included elements of

bad taste. Norma Niurka, however, came to the play's defense in The

Miami News Spanish'supplement by quoting Fando's stage designer,

Siro del Castillo: "We cannot allow inquisition tribunals in

the 20th century to tell us what we can choose. When we left

Cuba, we left .. so that we COULD CHOOSE."

The controversy surrounding Prometeo's two stagings of

works by Fernando Arrabal during this period, Fando

and Lis in Spanish (1976) and The Garden of Delights

in English (1978), conflated issues of decency and politics.

Arrabal, an important Spanish avant-garde playwright, was

branded a communist because of his anti-Franco position.

Critics cautioned potential theatergoers against going to

see The Garden of Delights because it included elements of

bad taste. Norma Niurka, however, came to the play's defense in The

Miami News Spanish'supplement by quoting Fando's stage designer,

Siro del Castillo: "We cannot allow inquisition tribunals in

the 20th century to tell us what we can choose. When we left

Cuba, we left .. so that we COULD CHOOSE."

If you live in Cuba...

Francisco Morín's famous 1978 staging of Virgilio Piñera's Electra

Garrigó by RAS was also blacklisted because the playwright lived in

Cuba. Although Piñera was completely ostracized in 1970s Havana,

the fact that he supposedly had not tried to emigrate made him

suspicious in some Miami circles and led to bomb threats.

The Herman Hesse quote included in the program could be read

as a commentary to the ongoing local controversy: "When

truth is threatened by struggles based on material interest and slogans . . .

then our only obligation is to save truth."

Garrigó by RAS was also blacklisted because the playwright lived in

Cuba. Although Piñera was completely ostracized in 1970s Havana,

the fact that he supposedly had not tried to emigrate made him

suspicious in some Miami circles and led to bomb threats.

The Herman Hesse quote included in the program could be read

as a commentary to the ongoing local controversy: "When

truth is threatened by struggles based on material interest and slogans . . .

then our only obligation is to save truth."

Santa Camila de La Habana Vieja

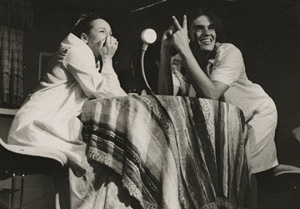

In 1979, Eduardo Corbé directed the Cuban classic Santa Camila de La

Habana Vieja by José Brene. This play premiered in Havana in 1962, and it was

one of the first plays in Miami to openly present on stage Santeria religious rituals

in a respectful manner. In spite of the importance of this production

and its success - its 40 showings were very well attended - the staging

raised debates in the city because the author resided in Cuba.

In 1979, Eduardo Corbé directed the Cuban classic Santa Camila de La

Habana Vieja by José Brene. This play premiered in Havana in 1962, and it was

one of the first plays in Miami to openly present on stage Santeria religious rituals

in a respectful manner. In spite of the importance of this production

and its success - its 40 showings were very well attended - the staging

raised debates in the city because the author resided in Cuba.

In less than

20 years, Miami became the border between Latin America

and the United States. With Hispanics accounting for 41% of the

population of Miami-Dade County in 1980. The face of Miami as the

capital of the sun was evolving. Throughout

these two decades there were scores of Cuban artists and theater

companies that thought of themselves as part of a larger international,

cosmopolitan scene. This last section tells the story of some of

those who actively participated in the cultural transformation of Miami into a world city.

and the United States. With Hispanics accounting for 41% of the

population of Miami-Dade County in 1980. The face of Miami as the

capital of the sun was evolving. Throughout

these two decades there were scores of Cuban artists and theater

companies that thought of themselves as part of a larger international,

cosmopolitan scene. This last section tells the story of some of

those who actively participated in the cultural transformation of Miami into a world city.

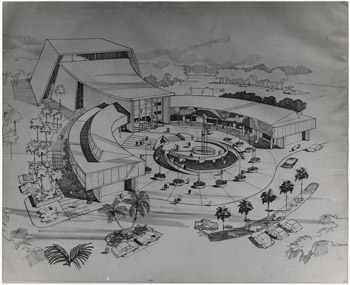

Manuel Ochoa's Inter-American Mission

The classical musician and composer Manuel Ochoa was probably the first

exiled artist to see the artistic opportunities that Miami could offer

as the gateway to the Americas. In 1969, Ochoa created with María

Julia Casanova the Centro de Artes de América (America's Center for

the Arts).

The classical musician and composer Manuel Ochoa was probably the first

exiled artist to see the artistic opportunities that Miami could offer

as the gateway to the Americas. In 1969, Ochoa created with María

Julia Casanova the Centro de Artes de América (America's Center for

the Arts).

The Center's mission was to promote cultural friendship and collaboration among all countries from the American continent. The founding Board planned for a performing arts center that included a theater as well as schools for dance, ballet, theater and painting. Ochoa continued to pursue his inter-American ideals throughout the 1970s but his vision would finally become a reality in 1989 when he established a truly multicultural arts organization, the Miami Symphony Orchestra.

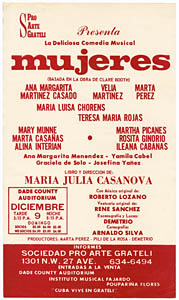

María Julia Casanova and Mujeres (The Women)

Casanova was another visionary and entrepreneur who imagined theater

in Spanish in Miami even before the 1959 wave of immigrants. She had staged

Claire Boothe Luce's The Women in Havana, a production that coincided with

the Coconut Grove Playhouse premiere of The Women in 1959. During a trip

to Miami, she met Dorothy Engle, The Women's producer and wife of George

Engle, who had bought the Coconut Grove Playhouse in 1954. Casanova had

the idea of bringing the Cuban production to Miami and staging it in

Spanish with the Coconut Grove Playhouse set. But the Cuban Revolution's

nationalization plans made her abandon the Hubert de Blanck theater she had designed and cofounded in Havana,

and in a matter of months, her life changed from a successful international

producer into a poor exile in Miami. She would have to wait till 1973 to

stage Mujeres at the Dade County Auditorium.

Casanova was another visionary and entrepreneur who imagined theater

in Spanish in Miami even before the 1959 wave of immigrants. She had staged

Claire Boothe Luce's The Women in Havana, a production that coincided with

the Coconut Grove Playhouse premiere of The Women in 1959. During a trip

to Miami, she met Dorothy Engle, The Women's producer and wife of George

Engle, who had bought the Coconut Grove Playhouse in 1954. Casanova had

the idea of bringing the Cuban production to Miami and staging it in

Spanish with the Coconut Grove Playhouse set. But the Cuban Revolution's

nationalization plans made her abandon the Hubert de Blanck theater she had designed and cofounded in Havana,

and in a matter of months, her life changed from a successful international

producer into a poor exile in Miami. She would have to wait till 1973 to

stage Mujeres at the Dade County Auditorium.

National Recognition for Grateli

By 1972, Sociedad Pro-Arte Grateli recognized Miami as a cosmopolitan center and wrote

a welcome message to its patrons in English.

Between 1974 and 1977, Grateli received four matching grants of between $10,000 and $15,000

each from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) through its Arts Exposure Program for

community-based arts organizations. Grateli was the first Spanish-language arts program

in Miami to receive an NEA grant.

community-based arts organizations. Grateli was the first Spanish-language arts program

in Miami to receive an NEA grant.

International Stars in Spanish-Speaking Miami

Capitalizing on the growth of Spanish-speaking communities in Miami, Grateli

expanded its repertoire to include theatrical productions and performances by

important singers and actors from the Spanish-speaking world. For example, the

Mexican actress Jacqueline Andere played the role of Margarita in Grateli's

production of Alexandre Dumas' La dama de las camelias (The Lady of the Camellias).

Grateli also invested efforts in concerts bringing to the city major singing stars

like Rocío Jurado, Sara Montiel, and Nati Mistral.

Mexican actress Jacqueline Andere played the role of Margarita in Grateli's

production of Alexandre Dumas' La dama de las camelias (The Lady of the Camellias).

Grateli also invested efforts in concerts bringing to the city major singing stars

like Rocío Jurado, Sara Montiel, and Nati Mistral.

Repertorio Español in Miami

The New York-based theater company Repertorio Español was the first to realize that Miami

could be an important theatrical venue for its productions. Repertorio teamed up with

local companies to bring their New York productions to Miami as well as to stage

them with local actors. In 1976, with Miami architect Mario Arellano, they remodeled

a space on Calle Ocho and opened Repertorio Español de Miami (Spanish Repertory Theater of Miami),

a 280-seat, modernly equipped theater.

a space on Calle Ocho and opened Repertorio Español de Miami (Spanish Repertory Theater of Miami),

a 280-seat, modernly equipped theater.

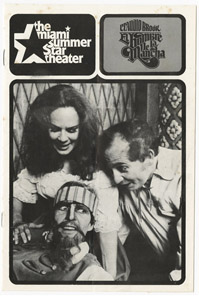

Man of La Mancha in Spanish

Miami was the city selected for the U.S. premiere of Man of La Mancha in

Spanish. In 1975, the Miami Summer Star Theater produced El hombre de la Mancha

with an all-star international cast, including Cuban-born performers Ana Margarita

Martínez Casado, Mario Martín, and Velia Martínez. It starred the Mexican actor

Claudio Brook, who had performed the musical on Broadway in English and in Mexico

in Spanish. The production's musical director and conductor Karen Gustafson,

was quoted in The Miami News: "The challenge of this theatrical first will be

to give Miami's Latin community an exciting and memorable musical event, while

offering English speaking audiences an experience similar to attending a foreign

language opera" (August 7, 1974, page 8A).

Spanish at the Coconut Grove Playhouse

The Players State Theater, resident company of the Coconut Grove Playhouse from 1977 to 1982,

also recognized the potential in Spanish-speaking audiences. They sponsored advertisements

for their shows in a variety

of Spanish-language production programs. In 1978,

the Coconut Grove Playhouse spoke Spanish for the first time when it staged Cuban

playwright Carlos Felipe's most important play, Réquiem por Yarini

(Requiem for Yarini, 1960). Felipe was then practically an unknown playwright in Miami.

His sister, the actress Rosa Felipe, joined a cast of well-known actors in

a production that received mixed reviews.

The Players State Theater, resident company of the Coconut Grove Playhouse from 1977 to 1982,

also recognized the potential in Spanish-speaking audiences. They sponsored advertisements

for their shows in a variety

of Spanish-language production programs. In 1978,

the Coconut Grove Playhouse spoke Spanish for the first time when it staged Cuban

playwright Carlos Felipe's most important play, Réquiem por Yarini

(Requiem for Yarini, 1960). Felipe was then practically an unknown playwright in Miami.

His sister, the actress Rosa Felipe, joined a cast of well-known actors in

a production that received mixed reviews.

Miami and the Performing Arts in Spanish

Cuban and other Latin American and Latino artists began

to recognize that Miami was an ideal setting for performing

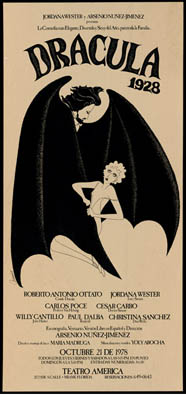

arts in Spanish. In 1978, Argentine actress Jordana Wester produced

Drácula 1928 with a cast that included actors of different Spanish-speaking nationalities.

New York-based artists started to come to Miami, bringing a new energy to the theater scene.

Famous Cuban director Herberto Dumé, for example,

moved to Miami at the end of the 1970s,

as did many other Cuban artists living abroad. Even opera stars such as Antonio

Barasorda, the renowned Puerto Rican tenor from the New York City Opera, chose to make Miami their home.

Miami Hosts Key International Theater Conference

Florida International University's Latin American Theater Symposium

in 1979 solidified Miami as an important venue for Latin American theater.

Some of the most renowned Latin American theater artists and scholars from

Latin America, Europe, and cities across the U.S. came to participate,

among them Osvaldo Dragún and Griselda Gambaro (Argentina), Isaac Chocrón (Venezuela), Carlos

José Reyes (Colombia), Alonso Alegría (Perú), and Luis Molina (Spain).

Local artists joined these international personalities in an event that

demonstrated that Miami had become a significant center for Latin American theatrical activity.

José Reyes (Colombia), Alonso Alegría (Perú), and Luis Molina (Spain).

Local artists joined these international personalities in an event that

demonstrated that Miami had become a significant center for Latin American theatrical activity.

The Mariel Generation

In 1980, Miami and its Cuban community were dramatically transformed by the Mariel Boatlift.

Many important writers and visual artists arrived during this mass exodus that saw

as many as 125,000 Cubans arrive in South Florida in a seven-month period.

In the performing arts, this included artists like Evelio Taillacq, Zobeida Castellanos,

Pepe Carril, René Ariza and Juanita Baró. Others, like Julio Gómez and Alberto

Sarraín, came during this period from Europe. They would all become protagonists of the fruitful 1980s.

Cuban Heritage Collection

University of Miami Libraries

University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida

Feedback