Amos Beebe Eaton:

A Soldier's Journal of the Second Seminole Indian War

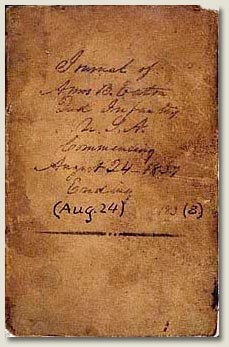

The diary of Amos Beebe Eaton begins on July 31, 1837 and concludes on August 24, 1838. This handwritten journal chronicles an extraordinary year in the life of a young lieutenant who served in the Second Seminole Indian War. The Eaton diary contains insightful personal observations, detailed reports on military activities, occasional sketches and drawings, and extensive commentary on the Seminole Indians and life in Florida. All notations are in Eaton’s hand, including the transcription of letters and military documents. Selected entries consist of brief or incomplete sentences, as military and weather conditions sometimes prevented Eaton from recording more complete thoughts and observations.

The diary serves as the core material for the Amos Beebe Eaton Papers, housed in the Archives and Special Collections Division of the Otto G. Richter Library at the University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida. This diary closely parallels the personal journals of another Florida soldier, Lieutenant John Pickell. Pickell, an 1822 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, served in the Fourth Regiment of Artillery, and his journals are located in the Library of Congress. Although Eaton and Pickell apparently never met, their diaries offer similar descriptions and observations.

The text of the Eaton diary is reproduced here with all spelling and punctuation intact. Brackets [ ] are used to identify uncertain words or phrases. Periodic gaps in diary entries are often noted by Eaton, who sometimes went days or weeks without recording a substantive comment.

Through his diary, Amos Eaton appears as an intelligent, inquisitive man. Eaton arrived in Florida as many northerners of the day, with little or no understanding of the unique geographical and cultural climate of Florida. His views regarding Indians, slaves, women, and other social and ethnic groups are also in keeping with the beliefs and customs of the era. Eaton’s comments on national political decisions, his deep religious convictions, concerns for his beloved family, and the uncertain military command structure and decision-making process provide entertaining and informative reading.

Numerous fine works on the history of the Second Seminole Indian War chronicle the military, political, and social issues that dominated this long and costly struggle. The United States Government spent more than $ 40,000,000 and the lives of approximately 1,500 soldiers in a war that lasted from December 1835 to August 1842. Amos Eaton arrived in Florida soon after Major General Thomas Sidney Jesup assumed command of forces in the state. Jesup’s arrival began a policy of "hunting down and capturing the Seminole in their camps," and "From early December 1836 to late January 1837 Jesup’s troops were engaged in combing the swamps, destroying villages, and driving to the east such Indian and Negroes as they failed to kill or capture." This was an extremely difficult logistical war for the U.S. Government, and the role of water transportation played a key role in moving men and materials. Steamboat activity also played a crucial role in Florida military operations, a fact supported time and again by comments found in the Eaton diary.

By the summer of 1837, however, "virtually all military operations against the Seminoles ceased." Jesup’s agreement with the Seminoles halted all but sporadic engagements. During this time period, the Army reinforced the troops in Florida as it prepared to remove the Seminoles to western lands. The Seminoles ultimately delayed their emigration from Florida and hostilities began anew. Eaton appears fascinated with the Seminole Indians throughout his stay in Florida. His introduction to the Seminoles is described in great detail. In an entry dated "7th and 8th November (1837) , shortly after his arrival at Fort Brooke, Eaton relates the discovery of Indian symbols on a road only a few miles south of the fort.

"There was a smooth place made in the sand on which was stamped an heart with two arrowheads, or acute angles crossing each other, & some of the observers thought there was discoverable the representation of blood trickling from the heart -- various interpretations were given to this by different officers, some quite playful. These marks were described to Old Abram, a celebrated Negro of great shrewdness formerly a slave of Micanopy, now in pay as a guide and interpreter to the army, who was born and raised among the Seminoles -- who said the cross marks was the private sign of Micanopy, the head chief in rank of the nation, & the heart the sign of some other Indian, & gave it as his interpretation that it indicated the desire for peace but that fear prevented their showing themselves..."

Eaton frequently commented upon the difficulty that the U.S. Army faced in delivering, maintaining, and transporting necessary supplies, arms and troops. As an officer with increasing responsibilities in this crucial area, Eaton’s observations are certainly worth noting. On November 11th, Eaton commented," The Army on this post is evidently too small to operate with the freedom & ease which would attend a sufficiently large & well equipped force...the different Departments of the Regular Army...do not draw together with harmony." Such criticism continued in subsequent entries. On November 17, 1837, Eaton observed, "One mistake committed in the preparation and arrangements for the present campaign is to leave the incipient contracts, hiring of Steam Boats, transports...to young and comparatively inexperienced officers..." Eaton’s frustration with limited progress in the war continued to grow, and on Sunday, November 26, 1837 he wrote, "If a man is to be in this country, which he is here, let him do his do, & be off again, & not exhaust his energies, cramp his powers of action, chill his armor & sicken his body by lying in camp, until eviscerated & listless he becomes useless..."

Among Eaton’s first significant observations on government policy and Indian negotiations, are comments he recorded on November 11, 1837. Eaton sadly remarked that the 178 Indians (Shawnees and Delawares) at his current post "have been very much deceived as to their compensation," and he noted that the government altered a promise of 45 dollars per month to each Indian down to 8 dollars per month, and offered a clerical error as an excuse for the confusion,

"This kind of trick & truckling on the part of the government of Washington is in perfect keeping with most of our dealings with the Aborigines -- these Indians will return home more than ever convinced of the faithlessness of the white man."

The constant struggle to survive in the Florida wilderness weighed heavily on Eaton’s mind. The danger of battle with the Seminoles, however, was only one threat. Soldiers also suffered mightily from the ravages of disease, malnutrition, and their own misadventures while stationed in camp. Eaton lamented on the tragic loss of life in a passage recorded on November 13, 1837:

"Almost every day the slow & solemn funeral march is heard, in playing the last sad memento to the dead soldier. How vastly wide has the earth of Florida opened her grasping jaws, to swallow up human life during this Seminole War! Ye Sons of the Hammock and Everglade, ye who in midnight’s stealthy hours. Slow creep and crouch along the brakey plain, what nerves your arm? Whence have you that successful & unassailable spirit that so bears up & makes ye strike so sure a blow."

Eaton also attempted to record the commonplace events of military life during the war, as time and duty permitted. He interweaves notations on routine activities, such as "Today I drew 40 new muskets for ‘D’ Company 2nd Infty," with ever hopeful observations on the course of the war, "...a delegation of Cherokee Indians were at St. Augustine, on their way to visit the Seminoles, with a view to dissuade them from further resistance to whites. It is earnestly to be hoped that they will be successful in their humane endeavors."

On November 18, 1837, Eaton succinctly states his preliminary assessment of Florida, "This is it, that millions of money has been expended to gain this most barren, sandy, swampy & good for nothing peninsula. The Seminole can never be put in a country so much secluded from the white man as here." A week’s experiences did not change Eaton’s impressions, and on November 26, 1837, he wrote, "Instead of being trotted, pulled, and hauled up & down the land coast & sea in this ‘disgraceful Florida War’ as it has got to be called, I would rather be well rid of the whole country & quietly seated in a more peaceful life."

The whirl of military duties, including the logistical challenge to maintain and transport military arms, equipment, and supplies throughout Florida demanded all of Eaton’s attention. On February 15, 1838, after almost a month’s hiatus from his diary, Eaton penned,

"Alas my neglected journal! The current of small events has so swiftly glided past, amidst the busy scenes into which I have been thrown. That I have guilt failed to keep up the thread of my diary of Florida doings. But this ... gap I have no time or inclination now to fill - and should I perchance to fill it, others would inevitably make their appearance to break the thread."

The many natural wonders of life in Florida did not escape Eaton’s keen eye, and on November 14, 1837, Eaton crafted a detailed sketch and description of "...a display of double rainbows the most brilliant & splendidly perfect of anything of the kind I have ever seen or heard of." The very next day Eaton also reported extensively on life in a military encampment. "We have in our camp all sorts of personages -- indeed I have never known a better place for studying man. Here he is bootless, idle & looked upon -- Here is the fat man, the lean man, the unwhiskered & he of the moustache. The laugher and the sad -- the man of prayer and the infamously profane -- here is the scholar and the consummate ass -- the man of rank, in state & majesty ordering the obedient hither & thither, and the infant in arms with timidity drawing his new bought blade..."

A devoutly religious man, Eaton chose to close his Florida diary with the recognition that "... after one year of chance & change I am by the kind mercy of my Heavenly Father, still alive & well -- tho absent from my dear family."

The diary of Amos Beebe Eaton serves as the surviving record of one man’s adventure as an eyewitness to the people, places, and events of the Second Seminole Indian War. The Eaton diary joins a compendium of other diaries and journals, government records, published histories, and related sources to illuminate a crucial period in the history of Florida and the evolution of U.S. Government-American Indian relations. Eaton did not write of his Florida days in his later years, either in letters to family and friends or in published form. He closed his journal as it began, with no undue ceremony or pretense, simply to document his thoughts and activities while engaged in a hostile situation far distant from home and family. Eaton proceeded to enjoy a life of distinguished military service, a career which began in large part on " this most barren, sandy, swampy & good for nothing peninsula."

The Amos Beebe Eaton site was curated by William E. Brown, Jr. and Ruthanne D. Vogel. This site was placed online July 6, 1998; last updated on December 18, 2006.